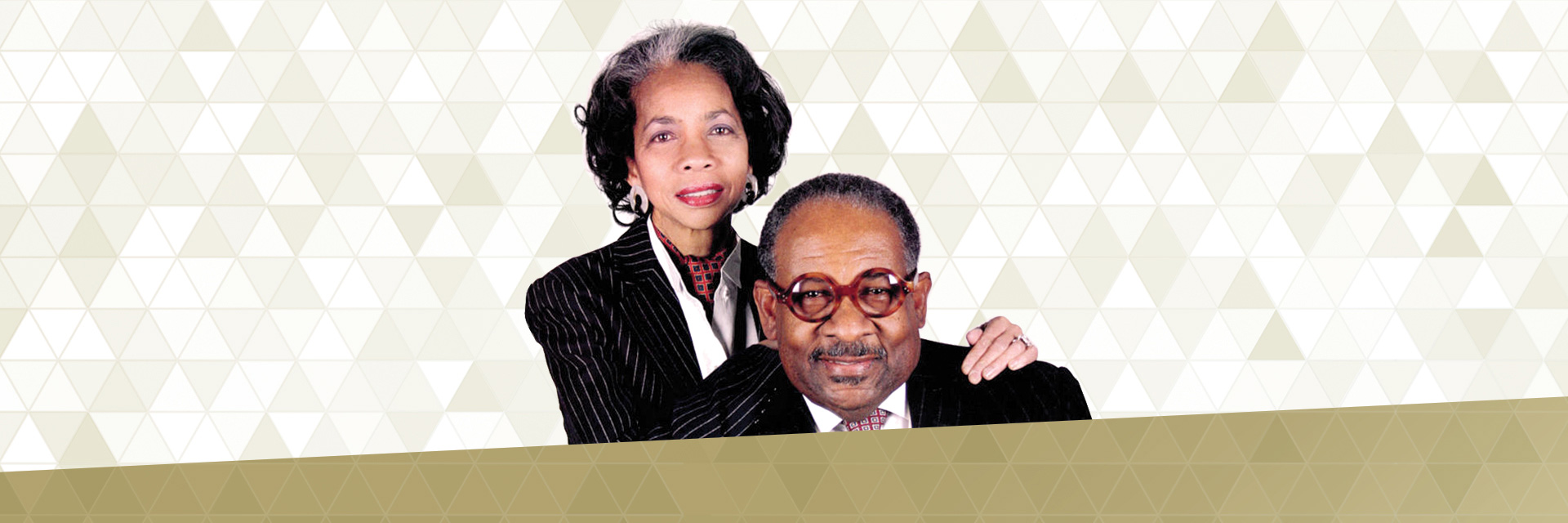

Bill and Ivenue: Georgia Tech’s Architect Heroes

Bill and Ivenue: Georgia Tech’s Architect Heroes

When the Stanleys walk into a Georgia Tech School of Architecture studio, no one else is able to stay in their seat. Whether they’re part of a studio jury or speaking at a NOMAS meeting, Bill and Ivenue Stanley are instantly mobbed by awed students and faculty members happy to see their close friends.

Bill Stanley (ARCH’72) and Ivenue Love-Stanley (M.Arch ’77) are famous architects who are Fellows with the American Institute of Architects and the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. Their legacy of work includes National landmarks like Ebenezer Baptist Church and the canopy attached to the busiest airport on the planet. In 1978, the couple founded Stanley, Love-Stanley, P.C. which is one of the South’s largest Black architectural practices.

In Atlanta, Georgia, they are something close to royalty. For close to 50 years, they have sculpted the city physically through their buildings and culturally through the communities they shape and care for.

Their influence on the way Atlanta looks and feels, even sounds, is because of their love for the city, Bill Stanley said. “I’m a fourth generation Atlantan, and Ivenue’s been here for 52 years. My family came here in 1890. We just thought, this is the place for us.”

They have a deep understanding of the city, and how developing the city through new construction and the evolution of existing buildings affects the lives of Atlantans. Their favorite projects, Bill said, are schools and churches, because those are the buildings that strengthen communities, and especially Atlanta’s African American communities.

“Light builds schools, we don’t do anything that doesn’t have a lot of light,” Bill said. “When Centennial Place Elementary School [now called Centennial Place Academy] was built it was a school of experimentation. It had experimental areas that had open gardens between classrooms, lots of filtered daylight. High demonstration areas where kids could fly balloons and shoot off rockets. B.E.S.T. Academy [at Benjamin S. Carson All Male Middle and High School] was one like that. Sylvan Hills Middle School the same way: wide open, big demonstration areas. Places where kids can be free. And that translates into colleges as well.”

The Stanleys have contributed to buildings on each of the college campuses in Atlanta, Bill said, including Spelman College, Morehouse College, Clark Atlanta University, Atlanta Technical College and Georgia Tech.

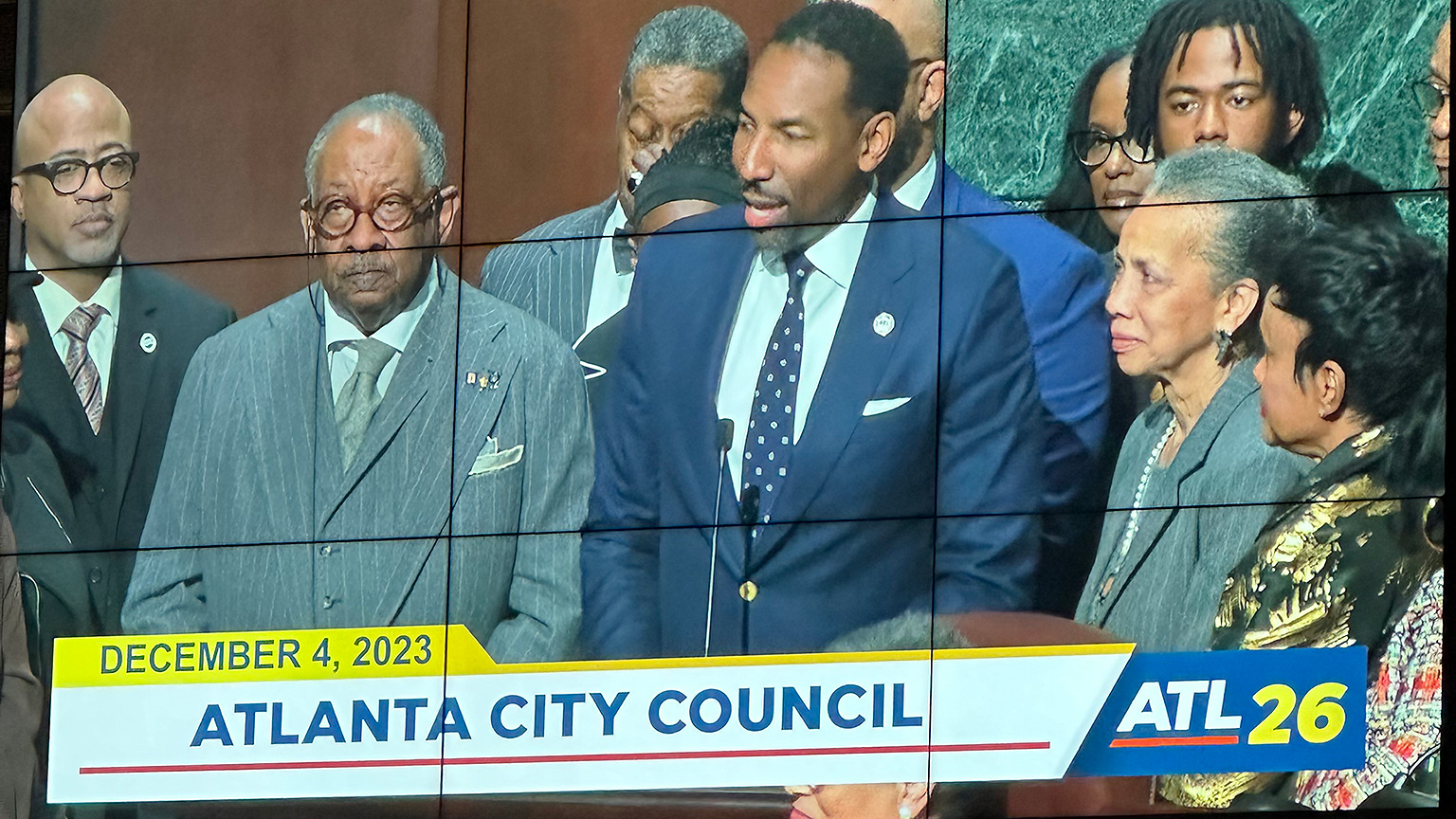

Mayor Dickens (a fellow Tech alumnus) and the Atlanta City Council officially proclaimed their contributions to the city last year.

“It is our belief that both of them, through their personal and professional contributions to the improvement of the Atlanta Way and the Institute deserve to be recognized for leading the way as trailblazers whose footsteps Black students have been following for over half a century,” wrote D.J. Terry, II, the Chief of Staff of the Atlanta City Council, in the December, 2023 proclamation.

At Georgia Tech, the Stanleys are cherished pioneers. They were the first Black man and woman to graduate from the Institute’s architecture program.

Bill Stanley was a founding member of the Georgia Tech Afro American Association, a student organization formed in the wake of the assassination of Rev., Dr. Martin Luther King. After she graduated from Tech, Ivenue became the first Black woman who was registered as a licensed architect in the Southeast.

They also made a transformative improvement to the campus through the Marcus Nanotechnology Building and the Olympic Aquatic Center, which they designed for the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta.

The couple have championed Tech’s architecture students through generous mentoring and scholarships for decades.

“Students ask us what they need to do to be successful,” Ivenue said. “They ask us how hard the profession is. And we’re really honest about it, how political it is and how tough it can be to find a job.”

They also ask about joining the National Organization of Minority Architecture Students (NOMAS), if they’re invested enough in their work, and if the Stanleys will give them an internship, Bill said.

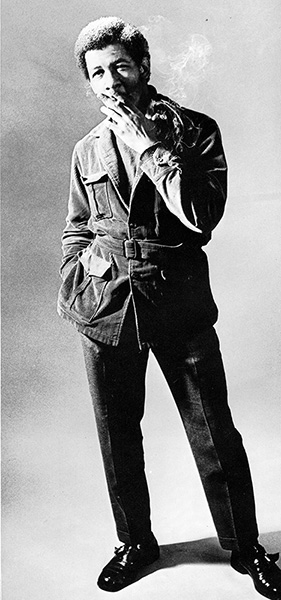

Photo: Blueprint/Georgia Tech Archives

Ivenue said it was important to both of them to give back to Tech and the community of students following in their footsteps. The scholarships they give to the School of Architecture are there to recognize the talent of African American students, she said.

They also advocate for campus displays of student architecture work. Bill said the College of Engineering has a tradition of being the 800-lb gorilla on campus, but the School of Architecture is the 15ft-tall giraffe. He believes architecture students’ work is worth sharing with other Georgia Tech students. And sometimes that work is too big to ignore.

“People don’t talk enough about Bertha,” he said.

Bertha was a pop-up pavilion that Bill and his fellow architecture students clandestinely erected in Harrison Square one night during his undergraduate years.

“We spent two weeks building these four by four panels, some of them four by eight, that we painted. There were paintings and drawings and slogans, all kinds of stuff.”

“The night we put it up, some athletes and fraternity guys saw us setting it up and they came and joined in, protecting us, going out to get us doughnuts and coffee. It was cold as Hell that night. It’s still in the yearbook.”

“And people were like, ‘Who did this? Oh! The architects did this’,” he said. “This is architecture. It’s about builds, it’s about social statements. And we stepped outside of [the East Architecture Building] and went into the heart of campus. You can see us, you can understand us.”